The evolution of work hours in industrialized countries over the past century tells a compelling story.

Six, ten-hour days a week were the norm until the 1950s when we transitioned to the now-familiar five eight-hour workdays. This shift was the result of substantial gains in productivity and the hard-fought efforts of labor movements to secure equitable shares of economic prosperity.

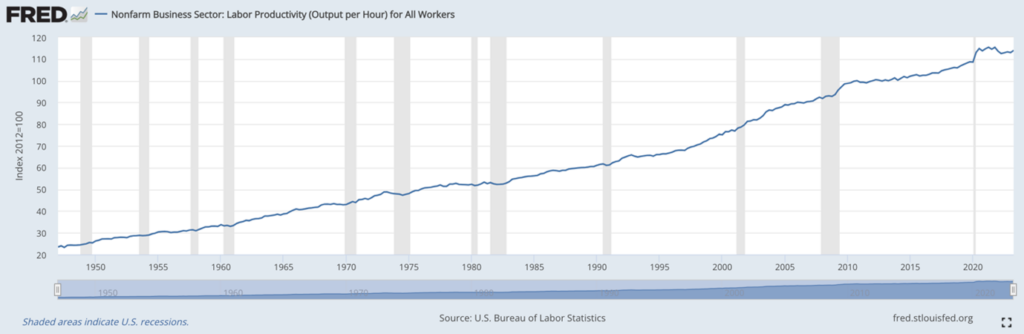

The mid-20th century brought with it the optimistic belief that we were marching toward a “leisure society” where a workweek of fewer hours and more paid holidays would become the norm. This vision failed to materialize, although recent breakthroughs in AI have resurrected the debate. American employee productivity has increased by a steady average of 2% for the past 70 years, and indications are that annual productivity growth could rise by up to 3.3% due to AI.

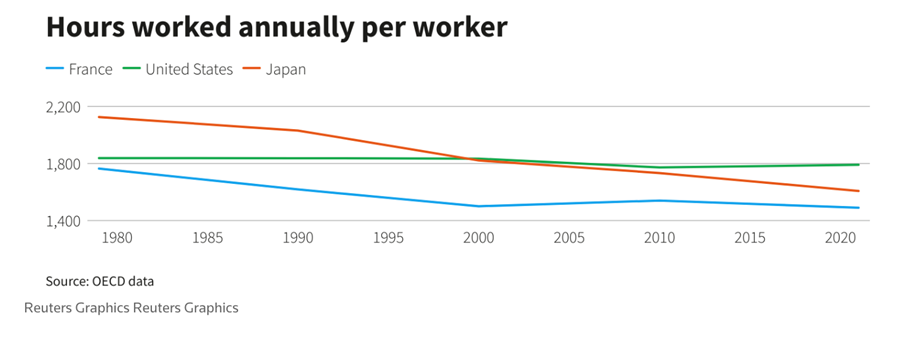

Have Americans managed to translate this increase in efficiency into fewer working hours? Yes, but not by much. U.S. workers have reduced hours worked annually by only 47 hours since 1979. French workers, by comparison, have reduced their hours by 274. Back in 1993, Juliet Schor asked why Americans are repeatedly choosing money over time in The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure.

The 100-80-100 model

Against this background, conditions seem ripe for a new workweek paradigm: the 32-hour, four-day workweek for the same compensation as a five-day workweek. This approach is often referred to as the “100-80-100” model, where employees receive full pay for working 80% of the usual hours while maintaining 100% productivity.

This concept has sparked interest and intrigue around the world. In Spain and Scotland, political parties have garnered electoral success by promising trials of a four-day workweek. Australia has taken a step forward by recommending a national trial of the four-day workweek through a Senate committee inquiry.

Success Stories in the United States

Several U.S. companies have embraced the four-day workweek with notable success. For instance, Microsoft Japan implemented a four-day workweek experiment in August 2019 and reported a 40% boost in productivity. Employees worked four days a week while receiving full pay, and the company experienced a significant reduction in energy consumption and operational costs.

Similarly, Shake Shack has been piloting a four-day workweek program in some locations since 2020. The results have been positive, with participants reporting improved work-life balance and retention rates. Shake Shack’s experiment served as an example of how this concept could work in the food service industry.

Where the 4-day workweek hasn’t worked

A BBC investigation found that the four-day workweek isn’t an automatic solution for every company. Engineering and industrial supplies company Allcap, for example, abandoned the experiment after reporting that employees had swapped “normal workdays” for fewer “extreme ones”, meaning they were exhausted when they came to their scheduled day off. In addition, when it was someone’s turn for a day off, a colleague would have to pick up the slack, while longer-term projects and strategic work “went out the window.”

Further, sectors providing face-to-face services to the public, often operating seven days a week and governed by health and safety concerns, may not have the latitude to reduce work hours. These sectors could face the necessity of implementing overtime or hiring additional staff, incurring extra costs. Public sector entities have been subjected to perennial efficiency savings, resulting in lean operations. Any reduction in work hours would necessitate higher labor costs, potentially in the form of overtime rates or additional staffing.

The applicability of the four-day workweek model to the broader economy is still an open question. The trials have generated optimism, but numerous hurdles remain on the path to widespread adoption.

Future Prospects

If the four-day model becomes the new standard, it is possible that employers who do not offer reduced hours may face difficulties in recruiting talent and remaining competitive.

This transformation is unlikely to occur overnight. The pace of change will be influenced by economic growth, productivity trends, and labor market dynamics.